BIO

By Jerilyn Fisher, Jewish American Women Writers.

1940 to the 1980s

Kim Chernin, 1998

Kim Chernin, Ph.D. has won acclaim for her numerous works of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry, including The Obsession, In My Mother’s House (Nominated for Chronicle Critics Award and chosen as Alice Walker’s Favorite Book of the Year in the New York Times, 1983), The Flame Bearers (1986 New York Times Notable Book) and the National Best Seller The Hungry Self.

She has appeared on Phil Donahue, Good Morning America, Charlie Rose, The Today Show and others. She has been featured on radio stations across the U.S., including NPR, KQED Forum and Larry King Radio. She appeared in the documentaries If Women Ruled the World: A Washington Dinner Party and Remembering the Goddess. Her articles have appeared in the New York Times Magazine, Focus Magazine and Tikkun. Her work has been featured in New York Times Book Review, LA Times, Newsday and other media.

Biographical Essay by Jerilyn Fisher, Encyclopedia of Jewish Women

On May 7, 1940, as Rose Chernin went through labor, she was reading a book between contractions: On the Woman Question, by Lenin’s comrade Clara Zetkin. Ushering Kim into the world with that book by her side, Rose may have hoped to inspire Communist vision and activism in the adult her baby would become; instead, she seems to have unknowingly augured her daughter’s commitment to and gift for writing about women.

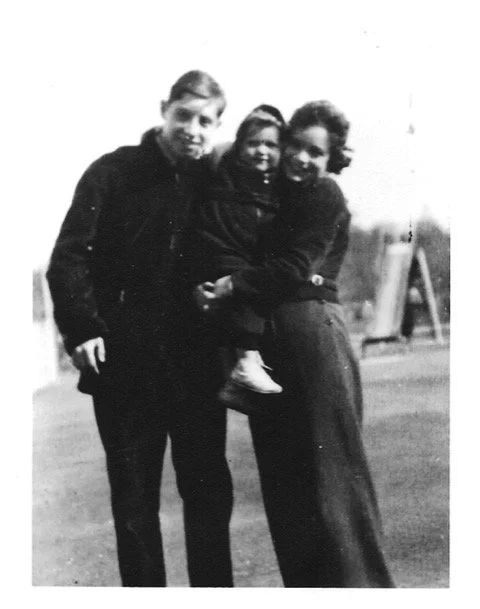

Nina, boyfriend and Kim, New York 1944

Born in the Bronx to two fiercely committed Marxists, Kim Chernin was exposed from the start to leftist teachings and impassioned political involvement. As a child, she marched with her mother, helped hand out Party leaflets, sang organizing songs, and overheard weekly Party meetings. Yet the Marxist teachings of Chernin’s parents did not result in her later commitment to revolutionary ideologies and activism; rather, she became a poet, a mystic, and an interpreter of women’s psychological experiences. These interests and capacities seem to have stemmed from the extended family circle of compelling storytellers.

For young Kim Chernin, one early source of inspiration for writing came from her shtetl- born grandmother, Perle, who created Yiddish tales for other women to use in their letters abroad. Chernin was also influenced by her storytelling father, Paul Kusnitz, who liked to recite Pushkin and delighted his daughter with daily “homespun tales.” Rose Chernin, another gifted teller of tales, sometimes left Kim bored with her didactic stories “about madness, revolution, the struggle to survive…” (Crossing the Border). Yet from her mother, too, Kim learned to harness and relish the power of the raconteur.

Kim (with braid) her parents and a a friend, Los Angeles 1948

While her mother’s work as a Party organizer etched the contours of Kim’s childhood, her early life was profoundly touched in a different way when her only sister, Nina, died of Hodgkin’s disease. For Kim, the loss was incomprehensible: She and her teenage sister had shared a room until the last unbearable months. Chernin believes that her inevitable struggle with a child’s confusion and guilt about Nina’s death was prolonged by the family’s inability to engage fully in mourning. Thus, confronting and resolving loss becomes a major artistic theme in her work.

Distracted with grief at losing her first-born, Rose Chernin became emotionally inaccessible to four-year-old Kim, the survivor. Trying to eclipse haunting memories of Nina, Rose moved the family to California, where other relatives had settled. There, in a rough central Los Angeles community, Kim attended school. By the time Kim was six, her mother had overcome the paralysis of depression and had resumed full-time work as an organizer for the Party. Then in 1951, Rose Chernin made national headline news when she was arrested for “advocating the overthrow of the government.”

Kim at rally in LA

RED DIAPER BABY: What was it like to grow up a child of the Communist Left in the 1950s? Proud of her mother’s dedication to the people, Kim also experienced social ostracism at school and lived nervously waiting for daily news about the outcome of her mother’s court appearances. From the beginning of Kim’s adolescence until she was eighteen years old, she came home from school each day not knowing if her mother would be at home or in jail.

Paradoxically, Kim’s youthful Marxist vision was deflated during a summer trip to Moscow after high-school graduation. Returning to Los Angeles, she quarreled with her mother more loudly than before, refuting Marx’s ideas as insufficient for revolution. Soon, Kim left home for Berkeley with a calling: She began to identify herself as a poet and a mystic, thus increasing the ideological distance between her and her mother.

Rose and Kim, LA 1948

Kim, age 17

In 1958, at age eighteen, Kim married, perhaps in part to reinforce this separation. Two years later, she went with her young husband to Oxford; in 1963, daughter Larissa was born. Within the next several years, the couple returned to America and separated. By this time, Kim had reassessed her feelings about her mother: When she was divorced, she changed her name, not back to Kusnitz but to Chernin, the last name of her mother and her mother’s mother, Perle. As an adolescent, Larissa would also change her name to Chernin.

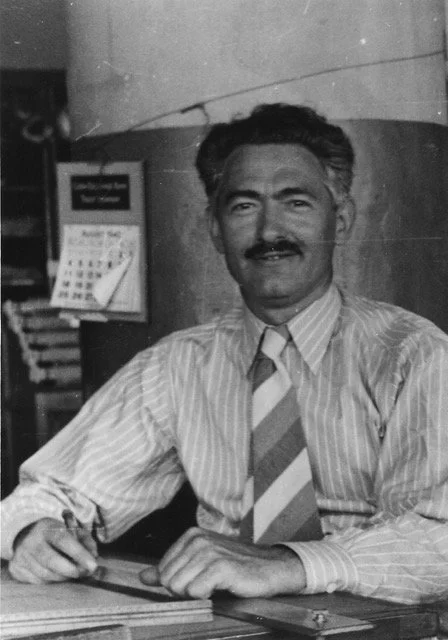

Paul Kusnitz, ca 1940

Nina and Kim, New York 1944

MOTHER AS MUSE: Throughout much of her life, Kim Chernin has wrestled with the desire to uphold or rebel against the ideals of her politically heroic, but often dogmatic, mother. These complex feelings about Rose Chernin have fueled not only Kim’s writing about her own life, but also her studies of contemporary women’s ambivalent responses to their mothers.

When Kim’s beloved father died in a car accident in 1967, Kim and Rose began to reconcile their differences, sharing their loss of the man who had always tried to build bridges between them. In fact, In My Mother’s House, begun a few years after Paul’s death, carries out his lifelong desire for peace between mother and daughter. But not until she wrote Crossing the Border does Kim Chernin give full voice to cherished memories of him. Most of this autobiographical story takes place in Israel in 1971, where Kim felt strangely drawn to travel. Responding to this mysterious pull, Kim went there to search for memories of her father. She also went hoping to satisfy her secret yearnings for communal Jewish life.

Today, twenty-odd years later, Kim Chernin is particularly moved by her identification as a Jew; she struggles to figure out what it means for a strongly feminist, goddess-loving daughter of Marxists to be a Jewish woman. While Chernin raises challenging questions about where women fit into the traditional observances and stories, she says that being Jewish defines her core self and “requires no external show of itself for [m[ to feel it and be held by it”; being Jewish, she continues, “has a kind of archetypal power; depth, vision, inspiration, meaning tend always to be organized for me in Jewish terms” (letter to the author, 8 July 1992).

JEWISH AUDIENCE: In 1987, for the Women’s Studies/Jewish Studies Convergences Conference at Stanford University, Kim Chernin gave a talk that was published in Tikkun. For the first time, she addressed a Jewish audience, speaking of her mother’s ambiguous relationship to Judaism and her own thoughts about what it means to be a Jewish woman. Reflecting on that talk, Chernin says, “It was the first time I had heard of myself as a Jewish writer. You can’t imagine my pride! No, more than pride. The inexplicable thrill to find out that I really was Jewish! Really! (letter to the author, 25 July, 1992).

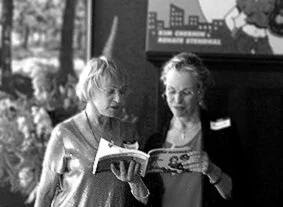

After returning to America from Israel in 1972, Chernin married again, and the marriage lasted six years. After the divorce, Kim Chernin and Susan Griffen lived-as-married for four years, residing with their two daughters. Then, in 1985, Chernin went back to Paris, where she renewed the friendship she had begun years before with Renate Stendhal, coauthor of Sex and Other Sacred Games. In their private lives, Chernin and Stendhal did meet in Paris; Chernin subsequently wrote an erotic short story about their second encounter, “An American in Paris.” Today, they live together in Berkeley.

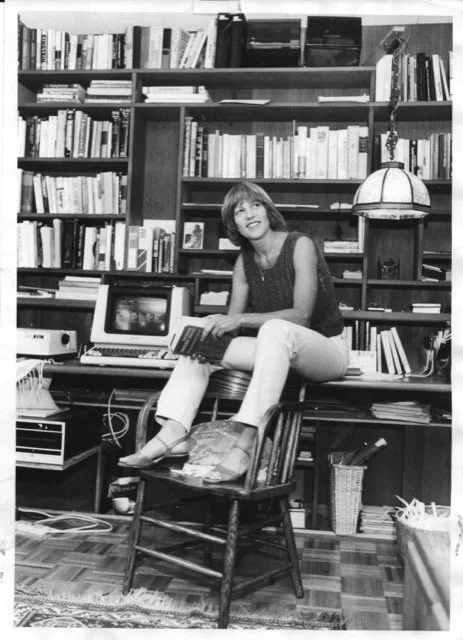

Kim Chernin, Berkeley, 1982

HOME-BOUND: At present, Chernin sees herself in a “home-bound period. . .” (Letter to the author, 8 July 1988. She writes and works as a psychotherapist in private practice, work for which she was trained psychoanalytically, and then in the interpersonal approach, with Otto Will, a colleague of Frieda Fromm-Reichmann and Harry Stack Sullivan. In 1981, Chernin began counseling as an adjunct to writing: Steadily, her practice has grown to occupy a place of central importance in her life. She counsels patients who suffer with eating and identity disorders as well as those in profound spiritual distress.

In addition to her work as a consultant and writer, Chernin’s attention is absorbed by her life with Renate Stendhal, by her daughter’s return to California, and by plans for building/growing projects (both real and metaphoric) in her home and garden. Working against her dreamy, reclusive tendency, Kim Chernin feels urgently challenged by desire for involvement in social activism. She lives with the tension between her mystical inclinations and the imperative to work for world change. From the fruitful dialectic bequeathed to her, Chernin tells her tales.

MAJOR THEMES: Reading Kim Chernin’s books, one is quickly struck by their thematic unity: Consistently, she writes about the female psyche, mothers, daughters, The Great Mother, food, loss, memory, and storytelling. In recent works, she also explores her sexual relationships, both lesbian and heterosexual (“An American in Paris,” Sex and Other Sacred Games, and Crossing the Border), characterizing women’s sexuality as dynamic, potentially creative energy that, when accepted and freed, will deepen our personal and spiritual growth.

Kim Chernin’s work spans a number of different genres: memoir, fiction, poetry, psychological study, and a psychosociological/religious study of women’s search for self. In writing nonfiction, she moves between ideas and compelling narrative accounts, her own and her clients’, weaving together intellectual discovery with personal stories. This form, a hallmark of Chernin’s literary style, works as an extension of her profoundly feminist perspective in which “the personal” carries great political and cultural importance.

The impact of her sister Nina’s death, and other significant losses suffered by her extended family, have prompted Kim to write analytically and imaginatively about women’s experience with different kinds of emptiness. In her studies of women’s identity and body image, Chernin explores their psychological responses to physical hunger and cravings, connecting that hunger to women’s emotional and spiritual emptiness, unnourished by patriarchal traditions. She contends that understanding women’s hunger–accepting it as a natural, healthy appetite for more than the scanty life portion women have been fed–can lead to discovery and satisfaction with the forbidden fruit of female knowledge and power. Women lovingly preparing food for (or experiencing interpersonal intensity as they eat with) other women recurs, motif-like, in several books and recurs imagistically in her poetry.

FOOD AND EATING: In Chernin’s view, the act of eating has become a uniquely meaningful source of memory for women unconsciously seeking union with the original, mother- nourished, infant-self. Seeing food in this way brings Chernin to believe that the modern daughter’s struggles with her biological mother can manifest themselves in the daughter’s overwhelming appetite: Food can represent to us a symbolic “return” to the powerful mother we once saw, the model with whom we once identified as female and from whom we once hoped to draw our own potential. With Reinventing Eve, Kim Chernin explores her understanding that, when biblical Eve compulsively bites what has been forbidden, she is hungering for “the power of the Mother Goddess . . . a deity who embodies the possibilities of female self- development . . . that female creative power all mention of which has been left out of the Genesis story” (xviii). Thus, Chernin uses psychological insight to cast Eve as our courageous, feminist progenitor in her extended revision of this Old Testament story.

STORY-TELLING: Chernin consistently shows that storytelling itself–one way to capture memory–can empower women, in particular, by retrieving and guarding a fragile, woman-centered past. She also has her narrators reflect on the arduous work of the storyteller. Often her narrators/storytellers feel ambivalent about their assigned task: In My Mother’s House, the daughter-writer is at first reluctant but soon, emotionally and artistically committed–to take the story Rose narrated and inscribe it onto the printed page. In the book, daughter-writer Kim understands the responsibility she has in having been “chosen to set these stories down” 18). Likewise, in The Flame Bearers, Rae Shadmi understands that having been so designated by her grandmother, she can no longer resist acting as the sect’s storyteller. In Crossing the Border, the older-self-as-narrator feels impelled to relate her version of the story about her younger self, the protagonist of the memoir.

Kim Chernin, 1982

Reflecting her family’s storytelling tradition, Chernin often uses a narrative structure that centralizes one tale and casts it within an interlocking web of other women’s stories. Often she spins her own story into this web. During the latter part of In My Mother’s House, Kim, who has previously heard the dale of her mother’s life, begins to narrate events that occurred in the to her from the time that Rose Chernin was imprisoned. In Crossing the Border, the narrator becomes split in two, and the present-day Kim Chernin takes over the narrative from her thirty-year-old self, the subject of the central plot/story. Through her memoirs, fiction, and the article appearing in Tikkun, Chernin reminds us that any story–family, biblical, and newspaper–is subject to multiple interpretations through the teller and the telling. Personal and cultural memories, inevitably subjective, reveal a great deal about the tellers. Through memories and what others learn from them, meanings and images reshape the future.

FICTION: In The Flame Bearers, Chernin shows the value of memory to retrieve the spiritual vision of the past. Challenging women’s exclusion in traditional Judaism, Chernin creates the Flame Bearers, a sect of women who are Jewish, yet not traditional observers; when these women read the Holy Book, they reconstruct Old Testament stories to reassert the days before women were excluded from Orthodoxy. Retelling and recording their stories is how the Flame Bearers’ traditions survive. In the novel, to hear the Flame Bearers’ woman-centered stories is to take responsibility for remembering them. To remember them is to prepare for retelling them to the next generation of women. Through the memory of Chochma, the Great Mother, the story of female power and knowledge lives on.

This symbolic carrying-on of stories and traditions through women in the family becomes another central theme in Kim Chernin’s work. The Flame Bearers centers on Israel (Rae) Shadmi’s gradual acceptance of herself as the sect’s next leader. First, she resists this role; slowly she grows into the knowledge that her grandmother’s ancient stories have all become “entangled around her very core” (“In the House of the Flame Bearers” 58). Similarly, In My Mother’s House displays the mother-to-daughter bonding between generations of Chernin women, bonding effected through Rose’s telling of tales and through daughter Kim’s ability to set them down.

At the same time that Chernin emphasizes the passing of traditions, especially from mother to daughter, she is also concerned with the daughter’s desire and need to be unlike her mother. Of In My Mother’s House, Chernin says: “Writing that book I was . . . preoccupied with the struggle to be different from my mother” (In the House of the Flame Bearers,” 56). In fiction, she explores powerful spiritual traditions of her grandmother, matriarch of the Flame Bearers. Psychologically, Chernin examines mother-daughter opposition and attachment in The Obsession, The Hungry Self, and Reinventing Eve.

Larissa, Kim, and Rose, 1986

With her latest memoir, Chernin continues to create narrative form that is provocative, sexually charged, and highly experimental. As a storyteller and a psychologist, Kim Chernin’s re-visioning of feminine consciousness expresses women’s hunger for personal, sacred truths about their maternal and erotic powers.

Survey Of Criticism

In light of the multidisciplinary content of her work, it is not surprising that no scholar has yet presented an overview of Kim Chernin’s writing. However, Chernin’s books have been widely reviewed: Responses most often focus on her experiments with narrative form and her feminist interpretations.

REVIEWS: Esther Broner is one who admires Chernin’s innovations in form. In My Mother’s House, Chernin’s most reviewed and highly acclaimed book to date, Broner describes as having a “Chaucerian” structure, with its many tales-within-a-tale format. Chernin’s narrative structure results, she says, in the readers’ experience of intimacy with the characters, as we find ourselves “listening in” on Rose and Kim’s private conversations. Similarly, critic Diane McWhorter hails In My Mother’s House as “ingeniously” structured and “operatic” in construction. Yet McWhorter also expresses frustration with the story’s irregularities in chronology and historical context. She contends that the book lacks sufficient social and historical context, suggesting that Chernin avoids the larger world by using narrative ellipses. The effect, according to McWhorter, is to recreate “the claustrophobic environment of her mother’s Russian shtetl.”

Similarly narrated in the fluid shape of a tale within a tale, Chernin’s psychological studies have enormous appeal for their accessibility. Most reviewers commend Chernin’s ability to make complex thought both readable and intriguing. This achievement, says Susan Wooley, lies partly within Chernin’s literary talent for writing with a “liquid” style. Reviewing The Hungry Self, Wooley applauds Chernin’s ability to create a “stunning word-portrait of women”; at the same time, she concludes that Chernin’s impressive writing talents seem to “plug gaps in research,” leaving some serious theoretical questions unresolved or undisputed. Anne Llewellyn Barstow, reviewing Reinventing Eve, agrees that “Chernin’s gifts are poetic and visionary . . .”; after enthusiastically offering this book’s praise, Barstow adds that at times the “experimental material and the religious re-visioning do not come together.”

What such comments suggest is that reviewing scholars who value her work sometimes take Chernin to task for not going far enough, wishing she could have applied her keen powers of insight to more expansive conclusions, or could have incorporated feminist research into her books of analysis and personal thought about women’s experiences.

Kim Chernin and Renate Stendhal, Pt. Reyes Station, CA 2014

COLLABORATION: Chernin wrote what is perhaps her most unconventional book to date, Sex and Other Sacred Games, with Renate Stendhal. In this fictional exchange of letters, and American femme fatale and a European lesbian meet and then write to discuss sexual “truths” concerning passion, attraction, pleasure, honesty, risk-taking, and power. Shana Penn in The Women’s Review of Books, values the rhetorical substance of the dialogue in which Claire and Alma thoroughly explore the reaches of their respective sexual identities and growing intimacy. A review in Publisher’s Weekly, on the other hand, questions the book’s sexual and political assumptions. This novel of heady conversation drew either unmitigated criticism or solid respect, depending on the reviewer’s interest in abstract, lengthy, feminist discussion of sexual politics and tolerance for an epistolary structure with only minimal suggestions of plot.

FICTION: The Flame Bearers, Chernin’s only work of pure fantasy to date, deserves special mention. Reviewed as a novel to be “read with delight by those who enjoy good ideological revenge,” Anne Roiphe describes The Flame Bearers as Jewish, feminist science fiction, celebrating its imaginative, mythical, woman-centered rendering of Hebraic tradition and God-wrestling. While admiring the book’s “richness of traditional knowledge that shines on every page,” Roiphe wishes that Chernin had resolved women’s historical exclusion from Judaism by creating more than “a turning of the tables.” That disappointment notwithstanding, Roiphe abundantly praises the book’s power and vision, hailing Chernin’s playfulness in using kabbalistic imagery and folklore to display the possible incompatibility of modern feminism and mainstream Jewish observance.

Kim Chernin 2017

Overall, Kim Chernin’s work reveals her commitment to understanding women’s inner lives and her fascination in exposing memory’s truthful fictions, with both personal and political life-story significance. Chernin’s latest memoir, Crossing the Border, has not been reviewed to date. In it she extends her penchant for crossing boundaries of narrative convention and continues to blend the “surprise and suspense . . . depth and humor” that Roiphe found in The Flame Bearers. Chernin intends to write a sequel to Crossing the Border.

– Jerilyn Fisher, Jewish American Women Writers

Re-use of information, text or images on this web site, including other pages within this domain, are permitted under the GFDL (GNU Free Documentation License).